PARTICIPATION IN THE CITY: HOW URBAN PARTICIPATORY INNOVATIONS ARE RESHAPING DEMOCRACY, GOVERNance AND TRUST (PAR-CITY)

PAR-CITY brings together a unique interdisciplinary set of 25 researchers to examine how and why cities respond to the key democratic challenges of our times.

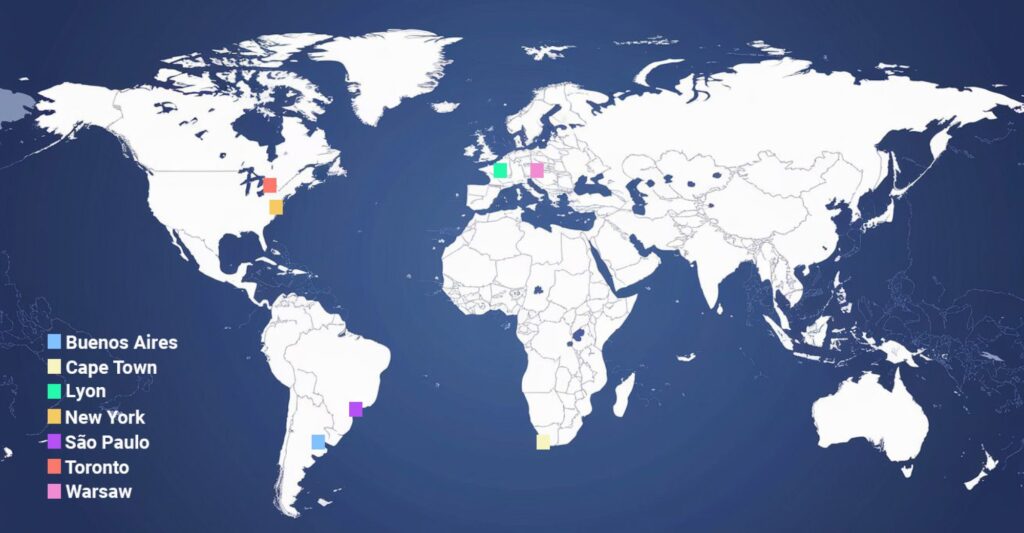

The project will undertake a relational comparison of 7 major cities covering 4 regions across the global south and north.

Each city has been chosen due to its promotion of one or more urban participatory innovations (UPIs) in recent years and will address the same central research questions in order to achieve three objectives:

1

PAR-CITY will establish the empirical significance of cities for responding to the global challenges of democracy, governance and trust.

2

The project will examine the role of digital media, tools and technologies in eroding or strengthening DGT in large cities.

3

The project will advance concepts, models and theories of DGT through the central notion of UPI.

PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATORS

SAM HALVORSEN

Lead PI - Queen Mary University of London

GABRIELA DE BRELAZ

Co-PI - Universidade Federal de Sao Paulo and NDAC/Centro Brasilero de Análise e Planejamento (CEBRAP)

AGNIESZKA KAMPKA

Co-PI - Warsaw University of Life Sciences

ZACHARY SPICER

Co-PI - York University

GUILLAUME GOURGUES

Co-PI - Université Lumiere Lyon 2

STEPHANIE MCNULTY

Co-PI - Franklin and Marshall College

ANNA SELMECZI

Co-PI - University of Cape Town

Buenos Aires has suffered multiple political and economic crises in recent years, alongside widespread loss of trust in politics. In response, an innovation has been the territorialization of democracy, as an idea and practice, centering the contested relations of city users through the struggle to appropriate and transform urban space. From disputes over green space, the upgrading of slums, the new urban code for housing, and other issues, the city has demonstrated the centrality of territory for understanding the mechanisms and processes through which DGT are built and sustained. Today, urban eighborhoods can participate through a range of participatory fora that span grassroots actors and institutions, including council consultation fora, city-wide meetings of urban participation, and a new network of decentralized participatory councils. Simultaneously, the city government has promoted the use of digital technologies and Buenos Aires was crowned as smart city of the year in 2021, promoting citizen engagement and participation as key to its agenda.

Like Buenos Aires, Cape Town is a deeply unequal city, with a persistent legacy of spatial apartheid and racial segregation. Recent years have seen loss of trust in the government and state institutions in every segment of society but, significantly for the post-apartheid era, the once highly mobilized poor black majority – the main constituency of the governing ANC and its coalition – has also turned away from the party of liberation. The compounding crises of large-scale corruption, high inflation and unemployment (especially youth) have manifested in decreasing participation in representative political processes. In response, and in the context of COVID-19, urban citizens innovated by setting up Community Action Networks to fill the gaps of social provision by state actors. A key innovation was to facilitate participation across racialised spatial divides, across rich and poor neighborhoods, demonstrating novel practices of solidarity. Attending to a different aspect of the crisis of democracy and building on previous research conducted by members of our local team in Hout Bay (Cape Town), we will inquire into how residents engage formal and informal channels of local urban governance to remedy the felt distance of government institutions from their everyday concerns (Anciano and Piper 2018).

Since 2015, Lyon, France’s second largest city, has been integrated into a larger “metropolitan” government of 1.4 million inhabitants. A local government elected by universal suffrage runs the Métropole, which is unique in France. Since 2020 it has been dominated by Green and left-wing parties, creating a unique commitment to participatory governance and restoring trust. Existing UPIs, such as participatory budgeting, have been revitalized, and a new generation of innovations, such as mini-publics, has emerged. Community organizing practices are also developing in several urban areas, in some cases supported by local authorities. Yet the implementation of UPIs is marked by territorial inequalities: the richest urban areas are staying away from this programme, while the poorest are maintaining old and outdated formats of citizen participation. Local political elites, social movements and inhabitants continue to innovate forms of citizen participation that attempt to avoid the pitfalls of participatory governance.

New York has one of the most dynamic and constantly evolving participatory ecosystems in the USA. In 2023, the mayor appointed a Chief Engagement Officer to oversee the multiple citizen engagement efforts in governance issues such as housing, environmental management, and migration. One of the most well-known innovations, NYC Participatory Budgeting (PB), has been rowing since 2011; today more than $30 million are allocated using PB. However, PB is not the only, or even most impactful participatory innovation in NYC. For example, the city has a network of 99 neighborhood Community Boards that are involved in participatory urban planning efforts. Grassroots organizations have also developed the “People’s Plan” to advocate for a just and equitable city. The US-based research team, in partnership with the NYU Urban Democracy Lab, has been engaged in and researching these innovations for decades. We will explore how UPIs around NYC are reshaping power and authority through contestation over spending and planning. This team will also host the culminating event: PAR-FEST.

São Paulo, the most populous city in Brazil, has been the stage for several participatory spaces and practices: councils, participatory budgeting, mini publics, citizens assemblies, public hearings, public consultations, and most recently, open government policy. Yet it has strong inequality and high violence and conflict. One response to these challenges has been the Open Government policy, implemented in 2014 through a Decree that established the Open São Paulo Program aimed at recommending legislation and promoting four principles: technology, participation, transparency and integrity (Brelaz et al, 2021). In 2016 the city joined the Local Open Government Partnership (OGP), a multilateral organization founded in 2011 to promote open government initiatives worldwide, and started co-creating and implementing open government action plans with civil society. The Brazilian team has been studying participatory practices in São Paulo for years, however the open government policy has not been analyzed in depth regarding its formulation, implementation and impacts achieved in the last 10 years. We will address this issue.

Like many Canadian cities, Toronto has sought to use smart technology and open government initiatives to innovate new digital pathways for citizens to access services and enhance the quality of service and policy delivery. Yet this has raised concerns from urban communities about loss of privacy, inadequate data governance protections and constant surveillance. These concerns were amplified through the introduction of Quayside – a project envisioned by Google-affiliated Sidewalk Labs that would have seen large portions of the city’s eastern waterfront infused with smart city technology. The project’s opaque data governance and privacy standards outraged urban citizens and eventually pressured the firm to abandon the project. Given the presence of these mega-projects and continued private investment in smart city technology, Toronto makes an ideal site to explore the participatory pathways available in smart city design and to examine digital cities as sites for citizen led governance tools.

The largest city in Poland, Warsaw is a key site of democratic conflict. Intense social polarization and low rates of social trust translate into local conflicts in the city’s public (including virtual) space. In response, the city government has sought to promote a pro-democracy agenda, e.g. leading the Pact of Free Cities and promoting local democracy within EU structures. The city government has developed several UPIs, e.g., smart city policy, public consultations, participatory budgeting, direct problem alerts. However, a key challenge has been to include people who are not permanente residents, such as temporary immigrants. In response, urban citizens have turned to digital space, social media in particular, to innovate new forms of urban participation. Through the lens of local protests over city planning, and youth digital participation, we trace the role of digitized tools and solutions. The Polish team (4) have common tasks: literature review, developing/adapting methods (document analysis, participatory practices, social media discourse), preparing reports, comparative analysis, participation in consortium meetings, publications, dissemination/promotion of project (e.g. website, conferences).